- Details

A fleshed-out design beats a great idea

Prototyped circuits beat SPICE simulations

Prototype PCBs from China beat schematics in CAD software

Lasercut acrylic panels beat Illustrator files

Things people have a good reason to pay fair price for beat reviewer freebies

Complementary collaboration beats a solitary vision

Rehearsal beats practice

Performance beats rehearsal

17/8/25

- Details

There's been a lot of discussion about the ethics of cloning old designs over the years, and it seems that the Behringer announcement of a Minimoog clone and seemingly inexorable march towards marketing it has stirred up the pot yet again. Therefore I thought that as a manufacturer of modules based on an old system I might as well put down some of my thoughts on the matter.

Firstly, copyright law gives little or no protection to a circuit design. Patents can, but they are expensive to obtain and so are the lawyers needed to enforce them. (As far as I know, Trade Dress (aka the intellectual property concept that protects the Coca-Cola bottle shape) has really only been used recently to try and scare away third party manufacturers from "proprietary" modular formats)

What happened in the synth community until at least years ago was the development of a sort of herd morality, where certain synth designs were viewed as sacrosanct and not to be copied without permission. The cynical amongst us might have seen a bit of a disconnect between the furore that shut down an effort to offer cloned VCS3 PCBs on electro-music (copying a design that was 40 years old and had not been in anything resembling serious production for decades) and cloners immediately and blithely disrespecting Korg's act of goodwill in revealing the circuit of the Korg35 filter core on the condition it not be copied. The fact that only one of the above belonged to a serious investment object was not lost on quite a few people.

Flash forward to this year, and Behringer's announcement they were intending to make bargain-basement clones of long-obsolete monosynths, starting with the Minimoog, and a polarised response between those who wanted a $400 Minimoog for themselves and those who felt it was somehow a violation of Bob Moog's legacy. Like most things, the truth lies somewhere inbetween. Apart from the words "Moog", "Minimoog" and the Moog logo, there is no intellectual property left in a Mini. The company which makes them has no relationship to the original Moog Music apart from acquiring its trademarks. Its creator passed away a decade ago. And yet - there is little expectation that a Behringer clone will anything but reductive, adding nothing to the art of the original but sacrificing quality, and a far cry from Korg's ARP reissues, which were done with the co-operation of ARP principal David Friend.

So where do we fit into all of this? I guess to start with, selecting a system to copy that has been defunct since 1983 with no prospect of semi-official revival and no curation of its legacy by its creator (who incidentally passed away in 2015 while the Capricorn Series was already in development) is one thing. But I also liked Grant Richter's test when developing the Noisering of whether what I do would "advance the state of the art".

The fact that the Aries system seemed to be Denis Collin's lost vision of merging the 2500's philosophy with the 2600's affordability, which deserved more of a legacy, was one thing. But most of all, I felt that the Aries interface, where modules had a massive array of inputs and outputs, could provide a real alternative to a lot of current designs where legacy circuits, regardless of their source or original application, are shoehorned into a default "two audio ins, one V/Oct, one attenuated CV" panel layout. Despite the size shrink from 9" panels to Euro, I feel the Capricorn Series has managed to honour the ergonomics and playability of the original.

As far as the rest goes, we are determined to bring an original slant to the other modules we do. If we do revive another ancient technology which still has its creator's attention, then it will be with their permission and involvement (watch this space ;-) )

Oh and those cloners who copied Korg's old work? I imagine a serious reality check when Korg themselves reissued the MS20. Sometimes the easy, lucrative option is not the safest bet!

17/4/18

- Details

The Eurorack system doesn't have much left in common with the Eurocard (and VME) standards that shared the same physical racking factor. In particular the modules no longer need to plug directly into connectors on a circuit board backplane, which is a good thing. The idea of carry-on modular systems would never have evolved if modern Euro systems were stuck with the 160mm-length Eurocard format found in the the Elektor Formant!)

One thing that has remained in the Eurorack standard and is *not* a good thing is the idea of circuit board backplane. What worked well for digital signal buses and computer circuit cards is not so hot for analogue modules that depend on a clean supply for best operation. Why? Synth modules depend on analogue voltages to send pitch control data-and a semitone is just 83.3millivolts in the 1V/octave standard. If a synth module uses the supply rails to power its tuning pots or internal current references and there are fluctuations on the power rails then that creates a problem, most commonly manifesting in the dreaded "module crosstalk".

There are two places this can originate. One is the power supply itself. Every power supply has a "load regulation" spec, which describes how much fluctiuating current draw on the supply output will change its output voltage.

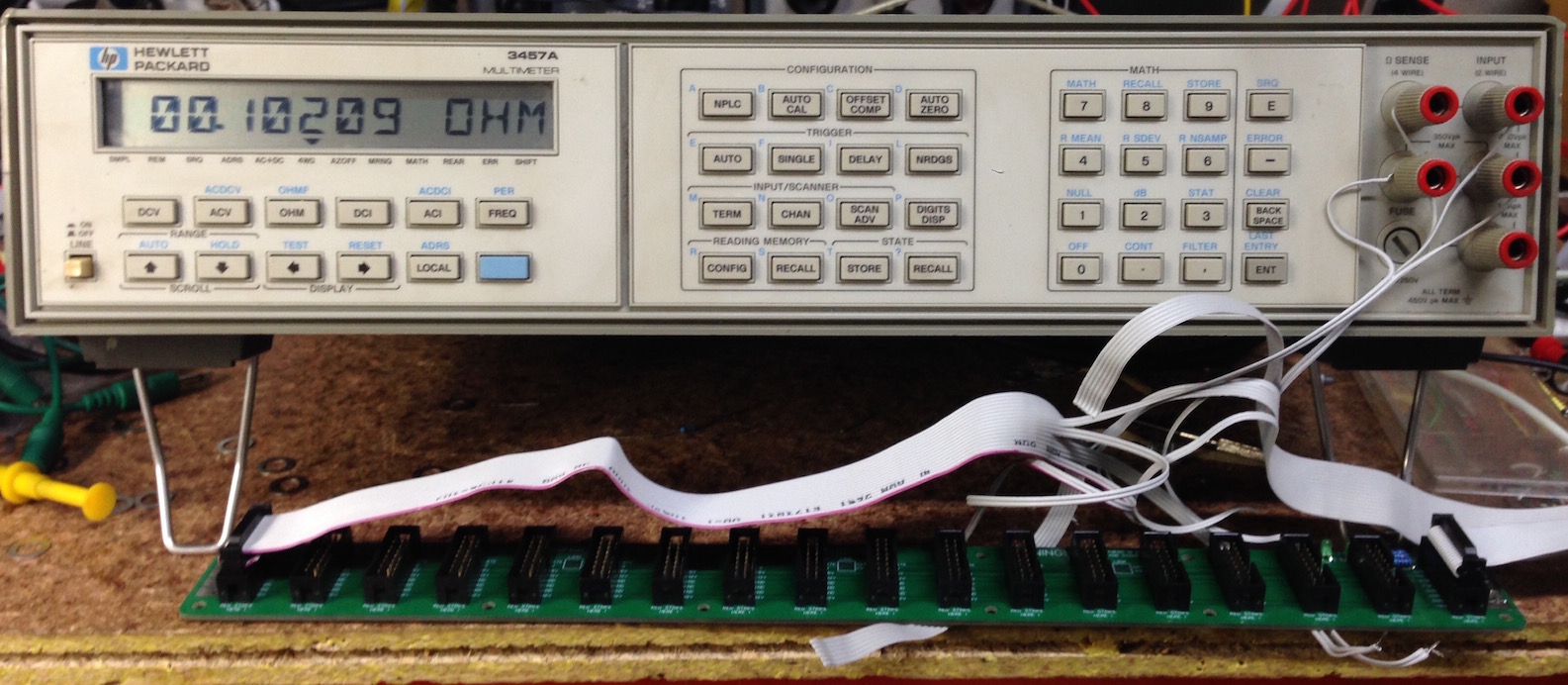

The other place is the distribution system. In a lot of electronic design the resistance of circuit board traces can be disregarded, but they still have a finite resistance. This matters when a sudden change in supply current (such as an LED turning on with 20mA current) creates a voltage drop across the finite resistance of a busboard line thanks to Ohm's law. How much is this "common mode resistance" which can affect other modules plugged in nearby? Let my new 30 year old toy tell a story...

The busboard with its +12V rail under test is one where I had trouble with module crosstalk, and the further from the power supply connection the modules were plugged in, the worse the problem was. The reading on the screen (0.1 ohm) offers a clue. Using 4-wire measurement means that the measuring current and the actual metering wires are kept separate until they enter and leave the busboard itself - power ribbons, and even the header connectors are kept out of the loop so just the resistance of the circuit traces and solder are measured.

So with our 20 milliamp LED blinking blinking furiously at the opposite end of the busboard to the power inlet, the 12 volt rail will be fluctuating by 2 milivolts for any module plugged in right next to it. For a lot of CV-controlled modules that will be audible as a slight warble. Add multiple modules with LEDs or other sources of current fluctuations (such as certain oscillators) and soon you'll have a real problem.

So what's the answer? If you look at other modular formats this is not so much of an issue, and it's no coincidence that Euro is about the only format that generally forces power lines to go through long thin PCB traces to supply a system's worth of modules. So, it doesn't have to be that way. Check this out for starters..and stay tuned to this site!

17/2/27

- Details

This has been a long trip of over 2 years of EAGLE wrangling, junked prototype boards, evolving design languages, and left turns prompted by sesquicentanarian test equipment found in a pawn shop. You ain't seen nothin' yet!

J